[ad_1]

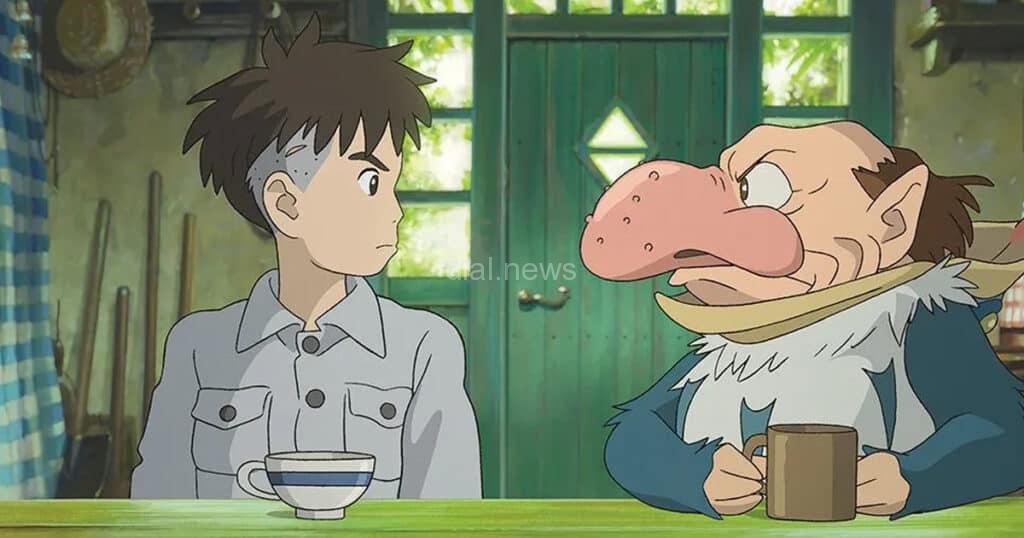

PLOT: After his mother is killed during WW2, a young Japanese boy, Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), is sent to go live with his Aunt, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), with whom his munitions factory owner father is trying to start a new family. Deeply scarred by the death of his mother and unable to accept his aunt, he finds himself distracted by a trouble-making grey Heron (Masaki Suda) who eventually whisks him into an alternate world of fantasy and danger that is tied to his ancestors.

REVIEW: We all have our blind spots regarding film history. I’m proud of the fact that I have a solid knowledge and love for both the Golden Age of Hollywood and classic foreign cinema, but I have one place where my film knowledge comes up glaring (and shamefully) short. I’ve never seen a Hayao Miyazaki movie. I’ve never been a major animation buff, making me an odd person to review Miyazaki’s presumably final film (and indeed, our resident Miyazaki expert will examine the film further down the line. Truthfully, I didn’t know what to expect, but it didn’t take long for me to get swept up into the Japanese master’s world.

In Japan, The Boy and the Heron was released without a trailer, and indeed, that’s the best way to experience the film as it defies easy classification. If it reminded me of anything, it was the 80s classic Labyrinth, in which a young person must quickly come of age to recover the family member they’ve always treated as a nuisance. Mahito is essentially a kind boy, and as per the culture, he’s never openly rude or dismissive to his aunt, but he shies away from her attempts to mother him, even when the pregnant Natsuko falls ill. He makes up a nasty head wound from a schoolyard brawl to get out of school, but in his new free time, he becomes obsessed with capturing a giant grey heron, who teases him and promises that he can lead him to his mother.

Eventually, the film takes a hard detour into a fantasy universe that, among other things, includes giant man-eating parakeets, a younger version of his mother, and his mysterious, missing, and wise great uncle. While deliberately paced, the film casts a spell over the audience right from the start. The visuals are gorgeous, with Miyazaki emphasizing the beauty in his animation, with the notable exception of the terrifying fire that takes the life of Mahito’s mother.

It’s good, old-fashioned storytelling and feels like the swan song of an old master, even using a metaphor about how one man’s art keeps an entire universe from collapsing onto itself. Indeed, some people probably feel that way about Miyazaki’s work and their own lives, and every moment of the film drips with inspiration and a genuine sense of wonder. Miyazaki’s making art not commerce, but given the rapturous reception from audiences at TIFF, one can assume The Boy and the Heron will do well in both categories. Indeed, it feels like a potential best-animated film contender at the Oscars, although I doubt Miyazaki cares about awards at this point in his career. He’s as celebrated an auteur as there is, and this feels like a farewell, even for someone (like me) new to his work.

[ad_2]