[ad_1]

And you needed access to the cover versions of Richard’s hits by artists like Elvis and Pat Boone. You needed to show the blandness of Pat Boone’s cover of “Tutti Frutti” next to the power of the original.

[laughs] As hard as he tries to swing it, I think he’s still waiting for the spirit to catch up with him.

Did you think about including parts of Little Richard’s ‘70s comeback period, or was the film always going to be about the way the ‘50s music carried forward through influence?

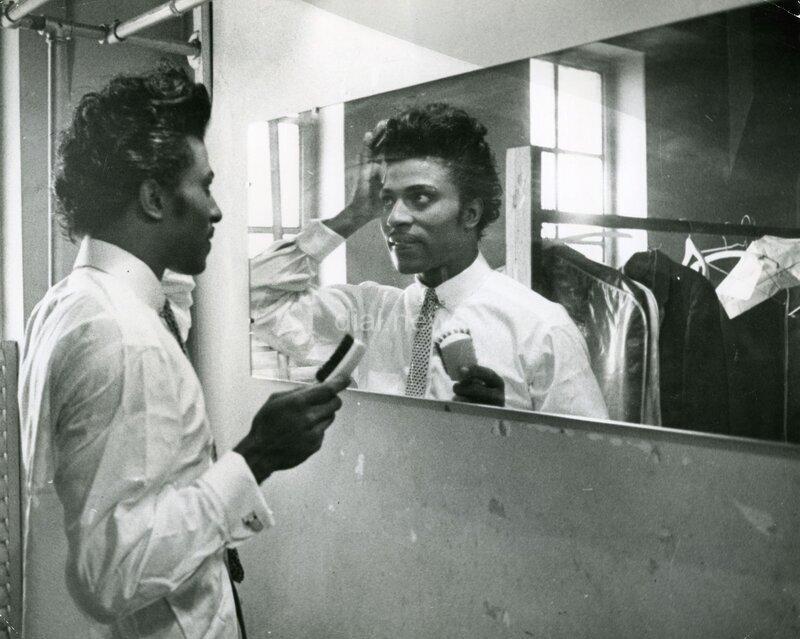

There were several tangents that were of interest, but with our incredible broadcast partner, we had a time limit. So it was always an internal question of what are the beats that are the most powerful, that move the themes along. Because with the idea of a Black queer man coming on the scene and wanting so much for himself, it was important for the audience to understand that he came into a system that did not want to benefit him financially or to really help further his career on the same level as his White peers.

I think his inability to have that complete access was ultimately quite devastating for his spirit. Yes, he said, ‘Oh I’m happy, they’re covering it.’ But you can see by the way he calls everyone out at Otis Redding’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame he’s harboring really sensitive feelings about all that he has aided and abetted for others and not received recognition for himself.

What were your biggest editing challenges?

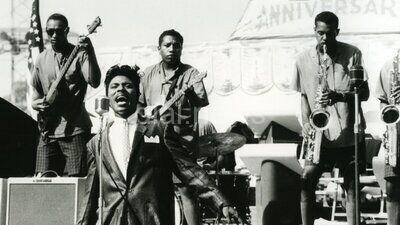

When I pitched this film, I always wanted to show two things. One is the connection to these moments in Richard’s life, that I think are seminal, where portals of possibility open up. And then two is that the artists are part of the continuation. As we see in the ending montage, his influence continues. It wasn’t just contained to one period. Because so many people don’t know much about Richard, they don’t see the vocal and performative elements that he introduced and that were his hallmarks, that have now been carried on by successive generations of artists.

I was really blown away by that final montage of contemporary musicians on stage, rocking outfits and moves and flamboyance that can so clearly be traced back to Little Richard. Did you know early on that the movie would end like that, and that was the narrative arc you were trying to create?

I would say halfway through, working on different chunks, thinking about the end, and realizing that even though we had spent so much time with Richard, this is a film where the present is in conversation with the past. Richard is not finite. His music and his presence loom large. And some of that presence has not been contextualized. It has not been introduced into conversations to say, ‘In 1955, look at this man. No one else is doing this.’ And we go to the present where it’s normalized, with no sense of the connective tissue of his acts of resistance and how they’ve been made accessible for artists now.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” is on CNN on Monday, September 4th.

[ad_2]